You may think of stress as the uncomfortable feeling of being overwhelmed; impending deadlines, upcoming bills, seemingly endless amounts of work. But what exactly causes this feeling? And what are its long term effects?

Let’s dive a little deeper into what stress is and how it acts from a physiological perspective.

What is stress?

Although you may think of stress as negative, it’s actually a necessary response to keep ourselves safe, and a healthy amount of it can actually be useful to boost our performance in different tasks.

Stress, at its core, is an instinctive and perfectly healthy response to a threat or stressor. When under attack, the body reacts to a threatening stimulus in a way that allows it to adapt and have the highest chance of survival.

How does stress work?

When we are faced with a threatening situation, the body’s systems quickly react to make us fit to face the threat. We commonly know this as a fight or flight response.

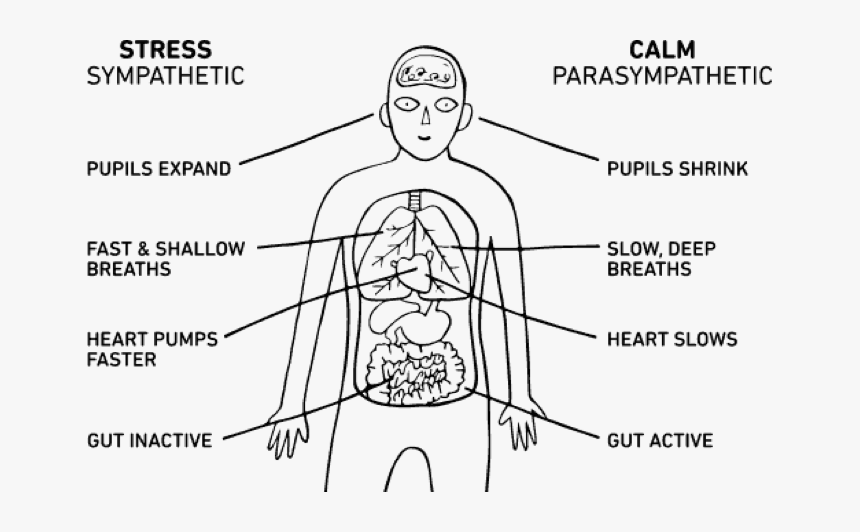

To understand this fight or flight response, it is important to look at the main functions of the nervous system. The central nervous system or CNS is constituted by the parasympathetic nervous system and the sympathetic nervous system.

The parasympathetic nervous system is known as the “rest and digest” system. It is in charge of autonomic functions like breathing, digesting, sleep regulation, and the like.

The sympathetic nervous system on the other hand is our waking, active system, also known as “fight or flight”. It is in charge of alertness, quick responses to stimuli, physical activity, and survival instincts.

In a nutshell, when faced with a stressor or threat, the sympathetic nervous system is on high alert while the parasympathetic nervous system takes the back seat.

When a threatening situation is registered by the brain, it sends a signal to the adrenal glands located above the kidneys to secrete three important stress hormones: cortisol, adrenaline, and norepinephrine.

These three hormones are in charge of preparing the body to either fight, flee, or freeze. Whatever the body deems to be the best response for the given situation in order to survive.

Adrenaline and norepinephrine are in charge of immediate arousal responses of the nervous system including1:

- Elevated heart rate

- Reduced blood flow to secondary systems to increase blood flow to muscles

- Elevated breathing rate

- Hyper-awareness and focus

- Active sweat glands

The release of cortisol into the bloodstream affects different systems and functions in the body:

- It regulates blood pressure, elevating it when a threat is perceived

- It affects metabolism, managing how the body uses different stored nutrients for energy

- Increases blood sugar to provide a boost of energy

- It inhibits body functions that are not necessary to immediate survival (immunity, reproduction, growth, digestion)

- Suppression of parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest functions)

Stress as a tool of survival

The physiology of stress is best seen in the natural world, so let’s look into an example of how stress is necessary for survival:

When an animal, say a zebra, for example, is sipping water calmly by a stream with no danger in sight, its hormonal and physiological systems are working normally. Its body is digesting the previous meal, its heart rate is at a normal resting pace, its muscles have just enough tension to perform the task at hand. Its hormones are balanced, and its entire autonomic nervous system is at a standard, restful yet awake state.

If this zebra suddenly looks up and realizes there is a lion stalking it from the nearby bushes, its entire physiology will change dramatically in a matter of seconds. Its parasympathetic nervous system will be subdued by the sympathetic nervous system shutting down any functions that are not absolutely necessary for immediate survival (eg. digestion and recovery). The sympathetic functions will kick in to their highest capacity. The zebra’s heart rate will spike rushing blood into the muscles for better physical performance, and its pupils will narrow into a laser focus vision. All energy that is spent in behind the scene activity such as reproductive health and immunity will be sent to the back burner.

The zebra is now as equipped as it can to deal with the situation. This is what we know as a fight or flight response. This is an all-hand-on-deck situation where all systems in the body come together with one purpose: to survive.

Assuming the zebra manages to outrun its predator and reaches safety, it doesn’t take long for its body to register that its life is no longer under threat. Shortly after this the autonomic nervous system will regulate again bringing the heart rate and blood pressure back down to normal, and restarting normal functions like digestion, reproductive function, normal breathing rate, and tissue recovery.

This kind of stress is known as acute stress. This term means that it is an immediate, aggressive response to a specific situation that ceases once the stressor is gone.

This type of stress response is a healthy, natural, and absolutely necessary function of stress. Without it, we would not be able to survive in the natural world.

Stress in everyday life

In today’s modern society it’s safe to say that most of us, unlike the zebra, don’t have natural predators to run from or fight with to stay alive. So how’s it that out of all creatures in the animal kingdom we’re some of the most affected by stress?

The problem with stress is that as much as we understand it on a rational level, our subconscious mind and body do not know the difference between an actual threat and a perceived one.

In other words, for the body, imminent death via lion can be comparable to the stress of an upcoming bill or deadline. So although that upcoming bill will most likely not kill you, your body truly does not know the difference, and since its only purpose is to keep you alive and safe it will go through the motions it needs in order to survive.

Chronic stress

We have plenty of acute stress moments in our lives. A car accident for example can trigger all of the normal stress responses. Intense emotional situations like the death of a loved one or a traumatic event also cause acute stress responses.

Chronic stress refers to long-lasting stress responses that are not specific to a trigger and don’t dissipate when the trigger is gone. With chronic stress, the responses are compounded and the body goes a long time without getting a chance to fully recover.

Sustained, chronic stress can lead to multiple health issues that can range from mild discomforts to aggressive and dangerous conditions.

How does chronic stress affect the body?

Chronic stress can have severe consequences on our health if left unattended. Like many chronic conditions, the more it stays and compounds, the more aggressive the effects can be.

Let’s look into some of the most common effects of chronic stress:

1. Heart and circulatory problems

Natural stress responses elevate blood pressure in order to send surplus blood to where it is needed (muscles mainly) to face the threat. With chronic stress, however, these levels don’t fall back to normal. Instead, they remain slightly elevated day in and day out.

Chronically elevated blood pressure can increase the risk of heart disease and failure, stroke, dementia, cognitive impairment, and other conditions.

2. Cognitive decline

Chronic stress has been shown to reduce synaptic activity in the brain. Over time this reduction in brain activity can lead to loss of memory, confusion, trouble concentrating, and reduced capacity to learn and retain new information. In the long term a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia.

3. Metabolic issues

Because stress hormones elevate blood sugar, extended exposure to these processes can lead to blood sugar-related metabolic disorders like hypo/hyperglycemias, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and diabetes.

4. Reproductive health issues

When the body is in a constant fight or flight state, systems that are deemed non-essential to immediate survival are neglected.

The reproductive system is one of these. When exposed to chronic stress women can experience amenorrhea (absence of menstruation) or irregular cycles. The hormonal imbalance that can come as a result of chronic stress can lead to fertility issues as well as a general lack of energy and vitality.

5. Mental health and illness

The strong effects that stress can have on all systems of the body can, directly and indirectly, contribute to mental illness. Elevated stress responses can affect the brain’s receptors to different neurotransmitters that affect emotional well-being like dopamine and serotonin. This can lead to an increased risk of different mental illnesses including affective disorders like depression and anxiety. The effects that stress can have on brain chemistry in extreme cases can even lead to psychotic disorders and addictive behaviours.

6. Chronic disease

Chronic exposure to emotional and physical stress has been linked with higher risk of development of autoimmune disease in women2. In fact, chronic stress is a major contributor to multiple chronic diseases.

Stress is linked with systemic inflammation, and inflammation is one of the common causes of most chronic diseases including autoimmune conditions, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and even different kinds of cancer.

Ways to reduce stress

Finding ways to reduce stress is key to living an overall healthy lifestyle, especially today when most of our lives are ruled by varying degrees of chronic stress. Here are some of the practices that can help reduce stress and revert the negative health effects of chronic stress.

1. Meditation and mindfulness

Mindfulness practices have a long history and are spread through many cultures. The practice of mindfulness focuses on bringing awareness to the present moment by focusing on the breath and observing the movements of the mind.

By bringing awareness to the breath, the nervous system can recalibrate. This will help bring the heart back to a healthy pace, lower levels of tension in the body, and allow for rest and recovery functions to restart.

On the other hand, training the mind to gently come back to a concentrated place of easeful observation can help reduce the ruminating tendency that keeps us stressed. This practice allows us to observe when worry and stress are taking over and gives us tools to self-regulate and mitigate the effects of compound stress.

Mindfulness has been shown to reverse many of the negative effects of chronic stress. Studies have shown that practicing mindfulness even in small amounts can help reduce cortisol levels in the body.3

Mindfulness also helps create neural pathways that support creative thinking, memory recollection, mood regulation, and cognitive capacity. It has also been shown to reduce the risk of chronic disease, improve interpersonal relationships, and support a balanced lifestyle.

2. Exercise

Exercise triggers the body’s release of endorphins, a set of compounds that create a sense of euphoria in the brain. In addition, exercise and physical activity help regulate and strengthen cardiovascular activity which can help prevent high blood pressure. A healthy level of physical activity will also regulate hormonal processes in the body which can help boost emotional mood, elevate energy levels, and improve overall health.

3. Therapeutic modalities

Sometimes support from professional practitioners can be one of the most helpful ways to cope with chronic stress. This is especially true for those who’ve compounded stress from intense emotional experiences such as traumatic, or stressful events that have generated a baseline for elevated levels of stress-related hormones.

PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) increases the risk of chronic stress issues4, so for people healing from or integrating a traumatic experience, professional trauma informed support can alleviate symptoms of chronic disease.

Professional therapeutic counsellors, massage therapists, and other wellness practitioners use an array of tools that help bring the attention and focus back to the present moment much like mindfulness. Tools such as somatic practices (movement and body-centred exercises), art therapy, music and sound therapy, have the ability to create a space of awareness and focus that can help regulate the nervous system.

4. Exposure to nature

Spending time in nature has also been shown to regulate the nervous system and reduce signs of chronic stress. Exposure to nature has been linked with elevated emotional states and enhanced stress recovery by regulating parasympathetic nervous system activity5.